The University of Wisconsin-Stout traces its history to 1891 and has undergone many fascinating changes over time, but it has always stayed true to its mission of providing practical, career-focused education.

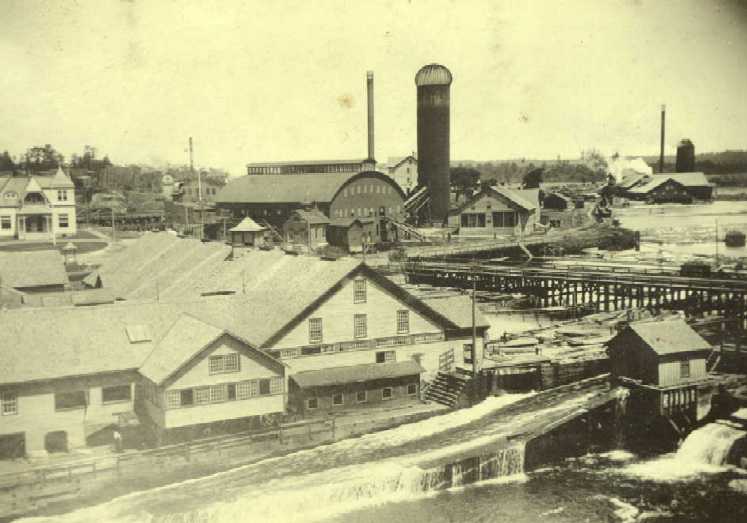

Menomonie was one of the largest cities in western Wisconsin as it entered the 1890s. In this city of more than 5,000, there were five newspapers, 12 hotels and boarding houses, several churches, and numerous retail stores. Industries ranged from such diverse businesses as brick and cigar-making to milling, and even a merry-go-round supplier. By far though, the city's largest employer was in lumber - the Knapp, Stout & Co Company.

For more than 50 years, the Knapp, Stout & Co. Company played an important role in the development of western Wisconsin. At its height, the company employed more than 2,000 people in Menomonie and the surrounding area. In Menomonie alone, the company had lumber mills, stables, a store, machine shop, blacksmith shop, grain warehouse and grist mill. Several of the owners made their homes in Menomonie, where they left lasting marks on the area's history. Wilson, Tainter and Knapp - the names that appeared in yesterday's social pages are today associated with many of Menomonie's buildings and streets. However, no name is more identified with the area than that of Stout.

James Huff Stout, the son of a member of the board of directors of Knapp, Stout & Co. Company, was born in Dubuque, Iowa. The heir to a large fortune, Stout served in several positions with the lumber company before making Menomonie his permanent home in 1889.

Stout had a continuing interest in manual training that may have begun when he was assigned by the company to work in St. Louis. In 1880, St. Louis became the home of the first manual training school in the country. According to legend, Stout agreed to pay for the education of a friend's sons in manual training. When he moved to Menomonie, he proposed to the city's common council to field an experimental program in the subject. It was difficult to turn him down. Stout offered a building, equipment and staff:

Stout had a continuing interest in manual training that may have begun when he was assigned by the company to work in St. Louis. In 1880, St. Louis became the home of the first manual training school in the country. According to legend, Stout agreed to pay for the education of a friend's sons in manual training. When he moved to Menomonie, he proposed to the city's common council to field an experimental program in the subject. It was difficult to turn him down. Stout offered a building, equipment and staff:

"I will place upon the school grounds, in a place designated by the Board of Education, a building of proper kind and size, furnished with all of the equipment necessary for the instruction of classes of boys and girls in the subjects included in the first year in a course of manual training. I will also pay the salaries of the necessary teachers, the cost of all necessary materials and supplies, and all of the contingent expenses for three terms, or for a time equivalent to three school terms, except such a part thereof as shall be paid by five hundred dollars, which is to be provided by the Board of Education."

Following the agreement, Stout and Menomonie school principal R.B. Dudgeon, traveled across the country, touring several manual training institutions. They sought advice and the views of others on manual training. By the time a two-story frame building was erected, three faculty members had been hired from the manual training school in Toledo, Ohio. They were Lillian Goldsmith, cooking and drawing classes; Mabel Wilson, sewing and dressmaking; and C.P. Friedman, woodworking and mechanical drawing.

When James H. Stout arrived in Madison to take up his duties as a state senator, he continued his work in the field of education.

Shortly after joining the Senate, he was appointed the chairman of the Committee on Education. In this position, he was instrumental in passing legislation that helped establish an agricultural and normal school in Menomonie, and similar schools elsewhere in the state. It was also as chairman that Stout became associated with Lorenzo Dow Harvey, one of the state's leading educators.

Harvey was born on a farm near Deerfield, New Hampshire, in 1848. Before he was two years old, his family moved to another farm in Wisconsin. At the age of 16, Harvey passed a county superintendent's examination and became a teacher in a one-room rural school. He managed to attend Milton College, in addition to his teaching duties and received a bachelor of science degree in 1875. While serving as principal at Sheboygan, he also studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1877. After a stint in business and education, Harvey served as president of the Milwaukee Normal School. His work and reforms at Milwaukee brought statewide attention. As a result, Harvey was elected to the state superintendency in 1898.

Harvey was born on a farm near Deerfield, New Hampshire, in 1848. Before he was two years old, his family moved to another farm in Wisconsin. At the age of 16, Harvey passed a county superintendent's examination and became a teacher in a one-room rural school. He managed to attend Milton College, in addition to his teaching duties and received a bachelor of science degree in 1875. While serving as principal at Sheboygan, he also studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1877. After a stint in business and education, Harvey served as president of the Milwaukee Normal School. His work and reforms at Milwaukee brought statewide attention. As a result, Harvey was elected to the state superintendency in 1898.

Due to the nature of their positions, Harvey and Stout often discussed questions on education. One of Harvey's special interests was the Stout training schools, and he took an active part in promoting them in Wisconsin and other states. When Harvey failed to be renominated for the state superintendency, Stout quickly offered him the directorship of the training schools. He used his influence on the local school board to have Harvey named superintendent of schools in Menomonie. Harvey was also made assistant cashier at Stout's bank so that his income would be the same as his state superintendent's salary. Harvey accepted the job in 1903.

Harvey brought to the Stout training schools a combination of dynamic leadership and professionalism that were to set the standard in manual training. Much of this was reflected in the bulletins that were issued following Harvey's arrival. In addition to the schools' course listings, the bulletins allowed Harvey and other leaders in the field to express their views on the goals of manual training in general and at Stout in particular. No doubt educators across the country looked forward to the bulletins, as they reflected the latest trends in an increasingly respected field.

At Harvey's suggestion, the Menomonie schools were reorganized in 1903. In addition to the Stout Manual Training School and the Kindergarten Training School, training schools "for the preparation of teachers of manual training and teachers of domestic science" were created. These training schools offered two-year certificates in manual training and domestic science.

The Stout training schools were already well-known in the state of Wisconsin when Harvey arrived, but in 1904, their reputation expanded on a national and international level. It was in that year that the schools entered an exhibit at the St. Louis World Fair. The exhibit won a gold medal, the only such medal awarded in that field.

Two years later, the training schools offered their first summer school. The courses were to meet the needs of "teachers of manual training, teachers of domestic arts and science, superintendents and principals of public schools, teachers in grade schools, training school students, and persons wishing to gain practical experience in various forms of crafts work." The first summer school attracted 11 students in manual training and nine in domestic science.

Under Harvey's guidance, the manual training schools were rapidly expanding in terms of students (243 in 1908) and number of programs offered. Success, however, was creating a problem in differentiating between the schools that were being supported by Stout and those that were being supported by the city. In an effort to clear up this problem, Stout, Harvey and William Ribenack (Stout's private secretary) signed the articles of incorporation creating the Stout Institute on March 20, 1908. One of the main goals of the corporation was to "provide facilities in the way of buildings, equipment, and teachers, through which young people of both sexes may secure such instruction and training in industrial and related lines of educational effort as will enable them to become efficient industrial, social, and economic units within their environment."

The creation of the Stout Institute crowned the first five years of Harvey's tenure. They had been innovative years and much had been accomplished. However, not all of Stout's and Harvey's experiments proved to be as successful as the two had hoped. For example, a trade school for secondary students introduced in 1908 proved to be short-lived. The Kindergarten Training School was discontinued in 1909, due to lack of administrative support.

The death of James Huff Stout in December 1910 was a great loss to the community as well as to the institute he founded. Stout died after a seven-month fight against kidney disease. In addition to his contributions to education, Stout was honored by people from Wisconsin for his work with libraries, hospitals, and the new field of conservation of resources.

Many feared that the Stout Institute would not long survive its founder. For many years, the institute had been running in the red; Stout paid for the deficits out of his own pocket. The senator's heirs, along with members of the Stout Institute Board of Trustees, asked the State of Wisconsin to assume the maintenance for the school in return for ownership. Fortunately, the concept of industrial education was gaining in popularity in Wisconsin at the time and the state agreed to assume control over the school in 1911.

With the death of its founder, the future of the Stout Institute rested largely in the hands of Harvey. Much of what the Stout Institute would become was shaped by his philosophy. In many ways, Harvey was the ideal administrator for the development of the institute. He was a firm believer in industrial education and a leader in educational rights for women as well. In addition, he was an innovator in new concepts in education, such as psychology. As an educator, he was universally respected, although not always well-liked. A member of his teaching staff later stated: "His followers and adherents recognized in him a bold, purposeful, clear-headed commander and they fell in line, even though sometimes rebellious at heart."

Student life at Stout was somewhat constricted under Harvey, but perhaps no more so than at other contemporary institutions of higher education. For example, for many years, students were required to wear uniforms and had a 7:30 p.m. curfew. On the other hand, there were several scholastic, social, religious and ethnic clubs in which students could participate. It was also under Harvey that a student annual (1909) and newspaper (1915) were introduced.

By 1912, enrollment at Stout climbed to more than 500, and it was apparent that the physical facilities at the institute had to expand. Through the efforts of Harvey and others, a trades building was erected in 1913 (now Ray Hall) and a home economics building (now Harvey Hall) was dedicated in 1917. The completion of these projects more than doubled the physical plant of the institute.

Even as the new buildings were under construction, Harvey began his campaign to bring a four-year degree program to Stout. After overcoming considerable opposition, the degree program was approved in 1917 in the areas of household arts and industrial arts. This approval resulted in the introduction of course work in history, sociology and several other liberal arts areas.

America's entry into World War I had profound effects on Stout. Enrollment at the institute dropped by more than half as many male Stout students answered the call to arms. On campus, men were required to take military drill, and women, Red Cross training. In 1918, a unit of the Student Army Training Corps was organized at Stout.

When the war ended, enrollment at the institute again began to climb. By 1923, the number of students reached a record level (589). Prewar activities and clubs also returned to campus. The Stout Institute, as well as the nation in general, was experiencing a period of unexpected growth and prosperity. Harvey had only a short time to enjoy the post-war life. He died June 1, 1922.

Upon his death, Daisy Kugel, director of home economics, stated: "By those who know Stout Institute, it will always be thought of as Dr. Harvey's school, for it is, indeed his, in the sense that it represents his educational ideas and ideals; that it is the embodiment of his dominating personality."

--Kevin Thorie

The names of the Stout Institute and Lorenzo Dow Harvey had been linked for so long, that at Harvey's death, many people wondered if a replacement could be found. Stout was a unique institution, and there was no pool of experienced educational leaders in the field to draw from. Fortunately, while conducting the search for Harvey's replacement, the Stout Institute Board of Trustees selected an able interim administrator in Clyde Bowman.

Bowman, a Stout graduate, joined the institute's facility in 1919 to become the first dean of industrial education. As acting president, Bowman was popular with the faculty and an attempt was made to have him retained as Stout's second president. However, due to political maneuvering and perhaps because he did not have an advanced degree, Bowman was passed over. He remained at Stout as the dean of industrial education until his retirement in 1953.

After nearly a year of debate, the Board of Trustees selected Burton E. Nelson as the second president of the Stout Institute. He began his duties in April 1923.

Nelson was born on a farm near Bedford, Pennsylvania, in 1867. At the age of nine, he was sent to the Pennsylvania Military Academy. Later, he attended the State Normal School at Millersville and Western Normal College in Illinois, where he received a bachelor of science and master of arts degrees.

Nelson was born on a farm near Bedford, Pennsylvania, in 1867. At the age of nine, he was sent to the Pennsylvania Military Academy. Later, he attended the State Normal School at Millersville and Western Normal College in Illinois, where he received a bachelor of science and master of arts degrees.

Although Nelson was making a fine record for himself in education, it wasn't until he became the superintendent of schools at Racine that he came to the attention of Stout administrators. Under his guidance, the first part-time vocational school in the country was organized.

One of Nelson's first decisions as Stout's president was to form the Stout Student Association. The association scheduled student activities, distributed activity fees and organized homecoming and commencement. Three years later, the Stout Student Council was created with members from the Stout Student Association as well as a representative from each of the four classes.

One of Nelson's first decisions as Stout's president was to form the Stout Student Association. The association scheduled student activities, distributed activity fees and organized homecoming and commencement. Three years later, the Stout Student Council was created with members from the Stout Student Association as well as a representative from each of the four classes.

Throughout his tenure, Nelson fought a continuing battle for the accreditation of the Stout Institute. In 1921, Stout applied for accreditation by the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, as well as the American Association of University Women. Accrediting teams, used to the needs of liberal arts colleges, had difficulty in approving some aspects of Stout, particularly the library and limited liberal studies offerings. Several years later, after much effort and expense, Nelson and his staff were able to get the institute accredited by North Central and other associations.

Early in his administration, Nelson faced a major crisis that reaffirmed the powers of the presidency that had been established under Harvey. The crisis began in 1927, with a bus trip to a basketball game at River Falls. When one of the buses failed to arrive, students were forced to cram into the two remaining buses - the first of many small disasters that occurred on the trip. The Stoutonia was quick to blame the chaperons for the trip's problems and the head of the household arts department, Daisy Kugel, in particular. Kugel and several of her faculty members threatened to resign unless Nelson forced the paper to offer an acceptable apology. Nelson, who was called back from his honeymoon to face the crisis, accepted the resignations of about a third of the faculty and did not interfere with the Stoutonia's content.

Many important student activities and traditions began in the 1920s, including growth in the number and sophistication of clubs. Phi Omega Beta became the first fraternity on campus in 1927. The first homecoming held in conjunction with a football game took place in 1922.

Many important student activities and traditions began in the 1920s, including growth in the number and sophistication of clubs. Phi Omega Beta became the first fraternity on campus in 1927. The first homecoming held in conjunction with a football game took place in 1922.

By the end of the 1920's, Nelson and his staff had done much to improve the Stout Institute. Positive steps had been taken to improve the library and the educational level of the faculty. Student life also improved as regulations on dress and dorm hours were relaxed. Unfortunately, the positive attitude that had taken hold on both the campus and the nation was about to come crashing down with the stock market.

The Great Depression was a difficult test for Nelson and the staff of the institute. Faculty members were forced to take pay cuts and building projects came to a halt. Enrollment dropped to a low of 400 in 1934. On the positive side, Stout received thousands of dollars from the Work Projects Administration for building maintenance and support personnel.

In spite of the financial difficulties imposed on the school by the Depression, Stout's academic reputation continued to grow. In 1932, Stout received full college rank and recognition. Three years later, a graduate program was introduced.

Alumni were largely responsible for the development of the graduate program. Stout graduates often found that they needed master's degrees for promotions. They asked Stout to develop a curriculum. A committee consisting of Clyde Bowman, Arthur Brown, Harry Good and Ray Wigen (known as the four horsemen) worked together to overcome accreditation problems and efforts by other institutions to restrict the program. In addition, they had no funds for extra staff and equipment. Despite the hardships, the graduate school opened in 1935, with master's degrees offered in the areas of home economics education, industrial education and vocational education. Ray Wigen served as the first dean of the Graduate School.

In 1938, Nelson introduced plans that would eventually lead to significant changes in the administration of the institute. Since its founding, the decision-making process at Stout had been in the hands of the president. The president had the final say on issues as diverse as hiring faculty members and scheduling lyceum appearances. As the institute expanded, the job became too time-consuming and Nelson appointed several faculty committees to share these responsibilities. It is important to note, though, that Nelson retained the power to accept or reject faculty recommendations. The first committees dealt with student relations, student employment, loans, publications, publicity, lyceum, library, health, physical education, athletics, admissions, credits and curriculum.

The student body at Stout began to grow slowly as the Depression eased its grip. In 1939, the institute enrolled 656 students. That year, at age 72, Nelson seriously considered the possibility of retiring. He had been Stout's president for nearly two decades and had seen it through the nation's worst economic crisis. Before he could decide, however, the United States entered World War II. In his diary, Nelson wrote: "I quit when Hitler does."

The war had a significant impact on Stout. Large numbers of the institute's faculty and students joined the military. Many did not return. Students who remained at Stout also participated in such wartime activities as the pilot training program and nursing. By 1943, intercollegiate athletics came to a halt due to a lack of male students (44 in 1943). In that year and the next, the traditional homecoming football games were replaced by kittenball and picnics.

Nelson tendered his resignation in June 1945, one month after the end of the war in Europe. He retired that fall.

The Nelson presidency has been criticized as being a stagnant period in Stout's history. Enrollment actually dropped during his administration and only Lynwood Hall, Nelson Field, and the Louis Smith Tainter House (known then as Eichelberger Hall) were added to the campus. Generally, the criticism fails to take into consideration the difficulties under which Nelson had to operate. There were the obvious factors such as the Depression and World War II, but Nelson also had to deal with a Board of Trustees from eastern Wisconsin. Some of the trustees had never visited the Stout campus. In a sense, they were unable to determine the needs of the institution. Perhaps Nelson should best be remembered for his efforts to get Stout accredited and recognized as an institution of higher education that was on a par with other colleges, while retaining its uniqueness.

The Nelson presidency has been criticized as being a stagnant period in Stout's history. Enrollment actually dropped during his administration and only Lynwood Hall, Nelson Field, and the Louis Smith Tainter House (known then as Eichelberger Hall) were added to the campus. Generally, the criticism fails to take into consideration the difficulties under which Nelson had to operate. There were the obvious factors such as the Depression and World War II, but Nelson also had to deal with a Board of Trustees from eastern Wisconsin. Some of the trustees had never visited the Stout campus. In a sense, they were unable to determine the needs of the institution. Perhaps Nelson should best be remembered for his efforts to get Stout accredited and recognized as an institution of higher education that was on a par with other colleges, while retaining its uniqueness.

--Kevin Thorie

During World War II, the government called on industrial arts leaders from across the country to contribute to the war effort. One site where this free exchange of ideas took place was the Armored Forces School at Fort Knox. At that school, the next three actual or acting presidents or Stout were brought together-William Micheels, John Jarvis and Verne Fryklund.

Fryklund, a graduate of Clouquet (Minnesota) High School, came to Stout as a student in 1914. A bout with smallpox and lack of funds almost forced him out. A local doctor, however, loaned him the money to continue and he graduated in 1916. Upon graduation, Fryklund worked in the Detroit school system. During World War I, Fryklund served in the National Guard. Following the war, he served at several schools while earning a master's degree from the University of Missouri and a doctor of philosophy degree from the University of Minnesota. In the decade prior to World War II, Fryklund taught at Wayne University in Detroit and at the University of Minnesota. It was during this time that the bulk of Fryklund's many books and articles were published. In all, Fryklund was the author or co-author of 35 books or bulletins and 70 magazine articles. Several of these publications were translated into foreign languages and are still in use today.

Fryklund returned to the military in 1942 as a lieutenant colonel and was made the director of the instructor training department at Fort Knox. He served in several administrative posts and received the Legion of Merit before being mustered out at the end of the war. On October 5, 1945, Fryklund became president of the Stout Institute.

In many ways, the Fryklund presidency would become the most controversial era in Stout history. When Fryklund arrived, the various departments on campus were divided into separate camps, jealously guarding their own responsibilities. The new president sought to overcome the divisions and to build unity. But in doing so, he created a wall of resentment with older faculty. They were less than eager to follow the order that Fryklund established. In later years, many faculty described Fryklund as "demanding, aggressive," and "stingy." Others praised him. They said Stout needed "the Colonel" to pull the school together.

Following World War II, Stout, like many other institutions, was ill-prepared to accept the large number of returning veterans that were taking advantage of the G.I. Bill. Enrollment at Stout more than doubled from 1945 to 1946. Fryklund was challenged to find faculty, housing, classrooms, laboratories and equipment for students.

The problem of housing was most acute. The administration responded by purchasing several barracks-style homes. A prefabricated unit consisted of a living-room kitchenette combination with built-in sink, running water, cupboards, a two-place electric hot plate and a built-in couch. Generally, these units were poorly heated and ventilated. They produced more fond memories than comfort. If occupants were not careful where they slept on especially cold nights their hair would freeze to the walls. In spite of those discomforts, many students remembered their years in the units as "the best days of our lives."

To overcome the shortage of teachers, promising graduate students were hired as instructors. The new staff members were then strongly urged to begin work on doctorate degrees in their spare time. Space for teaching the growing student body was not so easily solved. Money continued to be short. Before more funds could be allocated for buildings, enrollments began to drop as the veterans of World War II graduated. This drop slowed the building program and also led to temporary faculty cutbacks. Fortunately, enrollment again began to increase following the Korean War and, in 1955, the number of students broke the 1,000 mark for the first time.

To overcome the shortage of teachers, promising graduate students were hired as instructors. The new staff members were then strongly urged to begin work on doctorate degrees in their spare time. Space for teaching the growing student body was not so easily solved. Money continued to be short. Before more funds could be allocated for buildings, enrollments began to drop as the veterans of World War II graduated. This drop slowed the building program and also led to temporary faculty cutbacks. Fortunately, enrollment again began to increase following the Korean War and, in 1955, the number of students broke the 1,000 mark for the first time.

That same year, the Board of Trustees was abolished and Stout came under the control of the Board of Regents of the State Colleges. President Fryklund had opposed joining "the League," fearing Stout might lose its identity as a unique institution. With the change in administration, came a name change. The Stout Institute became Stout State College.

The administration also focused on the problems of curriculum expansion. In his history of Stout, Dwight Agnew, former dean of the School of Liberal Studies, related Fryklund's reactions to the questions raised by the study. Fryklund's words reflect the pride he felt in Stout and his fear that radical changes would destroy its unique position in higher education: "Stout has held to its two basic majors for more than 50 years despite the occasional regional pressure that we expand into academic areas. By concentrating on the two majors we have been able to study our problem and constantly improve our work... Stout has no plans for academic majors. We wish to concentrate on Stout's traditional assignment with supporting academic offerings."

The quality of student life improved under Fryklund's administration. The president had great respect for students and attempted to improve the educational experiences offered at Stout. Perhaps this was due to the financial and emotional problems he experiences as an undergraduate at Stout (Fryklund stuttered as a student). In response, Fryklund established Student Personnel Services in 1951, with Ralph Iverson as the director.

Three major building projects were either completed or planned in the 1950s. The first building, the Robert L. Pierce Library (now part of the Stout Vocational Rehabilitation Institute), was ready for use in 1954. Five years later, the Memorial Student Center (now the Communication Technologies Building), was dedicated. Fryklund Hall, the first major shop and classroom building to be erected on campus in nearly half a century, was completed in 1961.

Fryklund announced his plans to retire the same year the building that bears his name was completed. During his 16-year tenure, Fryklund supervised the transition of the Stout Institute from a stagnant small-town college to a medium-sized institution of nearly 1,600 students. More important, he set in place the tools that could be used for the tremendous growth that the institution would experience during the 1960s.

--Kevin Thorie

The 1960s would see an unprecedented increase in the number of students entering American colleges. The "baby boom" generation was coming of age. Technology also had a role to play. With jobs becoming more complex, America needed a better-educated workforce.

Students in the 1960s were a new breed. They questioned their parents' values and took a liberal stance on such issues as racial and sex discrimination, economic inequalities, and the war in Vietnam. When youthful ideals clashed with the political power of "the establishment," it would take a unique individual to reconcile polarities, create an atmosphere for learning, and administer a college that was expanding at a staggering pace. William J. Micheels was such an individual.

Micheels was truly a product of Menomonie and the Stout Institute. The son of a local businessman, he attended the Stout Institute following graduation from Menomonie High School. While at Stout, Micheels was president of the freshman class, played in the school band, lettered in football and basketball, worked on the "Stoutonia," and played in a dance band. After graduating in 1932, Micheels served in a variety of positions before going on to the University of Minnesota where he received a master's degree (1938) and doctorate (1941). Following World War II, Micheels returned to the University of Minnesota where he served as an associate professor (1946-1951), professor (1951-1954), and chairman of the department of industrial education (1954-1961). On September 1, 1961, Micheels became Stout's fourth president.

Micheels was truly a product of Menomonie and the Stout Institute. The son of a local businessman, he attended the Stout Institute following graduation from Menomonie High School. While at Stout, Micheels was president of the freshman class, played in the school band, lettered in football and basketball, worked on the "Stoutonia," and played in a dance band. After graduating in 1932, Micheels served in a variety of positions before going on to the University of Minnesota where he received a master's degree (1938) and doctorate (1941). Following World War II, Micheels returned to the University of Minnesota where he served as an associate professor (1946-1951), professor (1951-1954), and chairman of the department of industrial education (1954-1961). On September 1, 1961, Micheels became Stout's fourth president.

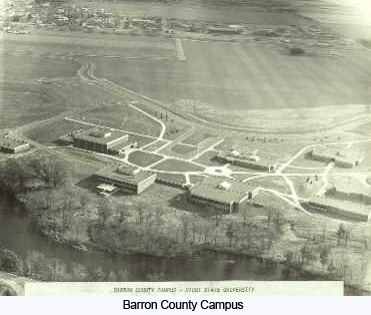

The Stout story during the 1960s is one of dynamic growth. At the start of the decade, Stout had a student population of close to 1,700 and a faculty of 107. By the end of the 1960s, enrollment topped 5,000. Faculty increased accordingly. Physical facilities and the number of programs offered also experienced dramatic growth. Micheels' administration also coordinated the operation of the Barron County Campus in Rice Lake, a two-year institution that grew from 116 students in the mid-60s to more than 400 by the end of the decade.

To deal with the surge, Micheels delegated more authority than his predecessors had been willing to. He believed in faculty governance. In addition to several senior level administrative teams, Micheels called for the creation of a faculty association in 1963. The purpose of the organization was to "study and act upon such policies as have or may be invoked by the President, either upon his request or by the determination of the Association."

To deal with the surge, Micheels delegated more authority than his predecessors had been willing to. He believed in faculty governance. In addition to several senior level administrative teams, Micheels called for the creation of a faculty association in 1963. The purpose of the organization was to "study and act upon such policies as have or may be invoked by the President, either upon his request or by the determination of the Association."

The influx of students led to the first of several administrative and instructional changes in 1964, "designed to unify the college and provide a framework for continuing growth." Many of the changes contrasted with Fryklund's philosophies, particularly in the area of academic programming. One change called for the creation of a School of Liberal Studies to join Stout's traditional schools of Home Economics and Applied Science and Technology. This was of particular interest to Micheels who felt that his education at Stout and the University of Minnesota had not properly equipped him in terms of "philosophy, ethics, and the so-called humanities." The addition of the new school provided another dimension to Stout's educational offerings.

The creation of several new academic programs in the 1960s helped ensure the growth of the student population. (The reverse has also been argued - enrollment growth led to the creation of several more specialized academic programs.) Micheels believed that it was the duty of the administration and faculty to "build on our strengths and strengthen our weaknesses." Several of the majors, such as art, were related to the early mission. Others, such as hotel and restaurant management and vocational rehabilitation, were driven by other needs and then nurtured by Micheels, other capable administrators and Stout's growing reputation.

In 1964, Stout State College became Stout State University. The name change was authorized by the Board of Regents who believed that the "state colleges had reached another plateau in their development."

School spirit soared when the football, basketball and wrestling teams won conference championships in the 1965-66 school year. However, as the decade wore on, there was a growing feeling of student unrest. Student disenfranchisement can be attributed to a number of factors, but by far the most important underlying cause was the war in Vietnam. From this issue, student concerns spread to such causes as academic freedom, faculty tenure and the right of students to have more input in the decision-making process on campus.

Student unrest was an important aspect of life at Stout in the 1960s, but it did not play as significant a role as it did on other campuses. In part, this can be attributed to the conservative nature of the institution. A large part of the credit for this, though, lies with Micheels. Micheels' policy was clear: "When dissent becomes such that it interferes with the operation for which we are in the business, then we will act firmly, we will act quickly, and people who dissent will have to allow us to dissent from their dissent." However, Micheels also took steps to give students an opportunity to express their concerns. One of the first programs that Micheels introduced was an independent studies course called "Personal Learning." The classes were held in the president's office with students and faculty members discussing their complaints and programs with their senior administrators. He also introduced a "box lunch" program that allowed students to sound off.

In the 1969-70 academic year, Micheels underwent surgery in an unsuccessful attempt to restore the vision in one of his eyes. While he recovered, John Jarvis served as acting president.

In the 1969-70 academic year, Micheels underwent surgery in an unsuccessful attempt to restore the vision in one of his eyes. While he recovered, John Jarvis served as acting president.

Micheels' return in March 1971 was, unfortunately, a short one. In November, he suffered a stroke. Micheels resigned three months later and was appointed distinguished professor by the Board of Regents.

Just before Micheels suffered his stroke, the nine Wisconsin State Universities, and the four University of Wisconsin campuses merged to form the University of Wisconsin System. This move was designed to reduce competition among the universities and to improve the overall quality of education. (The title for university heads changed from president to chancellor).

The newly named University of Wisconsin-Stout was guided by acting Chancellor Ralph Iverson during the transition. Iverson came to the campus in 1946 as an instructor in psychology and secondary education and had served as director of Student Personnel Services and vice president for Student Services.

The newly named University of Wisconsin-Stout was guided by acting Chancellor Ralph Iverson during the transition. Iverson came to the campus in 1946 as an instructor in psychology and secondary education and had served as director of Student Personnel Services and vice president for Student Services.

During the Micheels administration, Stout experienced dramatic change. Its evolution was made possible through the vision of the able president and his faculty and staff. Due to his failing health, Micheels did not have the opportunity to realize all of his goals for Stout. It would become one of the major tasks of his successor to solidify the growth of the institution and determine its future role.

--Kevin Thorie

Robert S. Swanson was named to head Stout in September 1972, following an extensive nationwide search. A native of Superior, Wisconsin, Swanson was born October 3, 1924. Swanson's father, an industrial arts teacher, first brought his son to the Stout Institute in 1937. Swanson returned as a student in 1942. His stay was short-lived, however. He enlisted in the armed forces December 1942 and left for active duty the following spring.

During World War II, Swanson served in an anti-tank company in France and Germany, receiving the Bronze Star and ending the war as a platoon sergeant. He was discharged from the Army in April 1946.

Swanson returned to Stout in 1946. That was a time of burgeoning enrollments as hundreds of other returning veterans also entered the institute. In his junior and senior years, Swanson served as a teacher to bolster an expanding instructional staff. When he entered graduate school, Swanson received a half-time faculty position. Swanson completed his master's degree in 1950 and was immediately hired as a full-time instructor. One year later, he began work on a doctorate at the University of Minnesota, receiving the degree in 1955.

In 1958, Swanson was named the chairman of the woodworking department (soon to be called the wood technics department). Later, he became assistant dean and then dean of the School of Applied Science and Technology. In 1966, he became the dean of the Graduate School. Six years later, Swanson received the appointment of chancellor of University of Wisconsin-Stout.

The new chancellor faced a wide range of problems and opportunities as he assumed office, but perhaps none was more significant than determining the future role of Stout. The rapid expansion of the student population and programs during the previous decade, combined with the merger of Stout into the University of Wisconsin System, provided an opportunity for the institution to maintain its historic purpose or to assume a new role. Swanson, due to his long association with the institution, chose to interpret his selection as chancellor to be an affirmation that Stout would retain its unique position in higher education. During his inaugural address, Swanson said: "Let it be known, that we do concern ourselves with the preparation of people to earn a living upon graduation. And let us further admit, with pride, that we do this because we specialize in fields which have a need for our graduates and because we do prepare people well to do their jobs."

That position was further clarified when the University of Wisconsin System requested that Stout prepare a mission statement to outline its role and goals. In part, the mission statement read: "the university should offer focused undergraduate, institution-wide programs related to professional careers in industry, technology, home economics, applied art, teacher education and the helping professions with the goal of meeting statewide needs for specialized curricula in these areas."

The new chancellor and his staff had to face an entirely different kind of problem when the administration building was the scene of a student sit-in during the spring of 1973. Students participating in the sit-in demanded hearings for a non-tenured faculty member released by the university. For close to 30 hours, the students expressed their grievances to the chancellor, vice chancellor and other administrators. The protest eventually ended peacefully and efforts were made "within the system" to change the Board of Regents' policy on tenure.

A persistent and frustrating problem that the Stout administration faced through much of the 1970s and 1980s was that of enrollment caps. In the mid-70s, the UW System decided that due to changing demographics, the universities in the system must prepare for declining enrollments. As a result, colleges were forced to place a cap on enrollment. This worked well with several universities that were indeed facing a decline, but for Stout it meant having to deal with the frustration of turning away thousands of students.

The enrollment caps, in turn, meant that the resources allotted to Stout by the state were relatively fixed. Even so, during the Swanson administration the campus saw extensive development in its physical facilities. In addition to major remodeling programs, six new buildings were added: Applied Arts Building, Library Learning Center, General Services Building, Heritage Hall (Home Economics Building), Memorial Student Center and University Services Building.

During the Swanson administration, there were dramatic changes in many academic programs. The number of concentrations offered within a degree program expanded greatly, largely in response to the increasingly specialized needs of business and industry. However, the traditional programs of industrial education and home economics education experienced dramatic drops in enrollment during the 1970s.

The composition of the student body had also undergone extensive changes over the last two decades. During these years, the number of international, learning disabled, handicapped, minority and non-traditional students grew significantly. In addition, several hundred Stout students participated in study abroad programs.

In his address to faculty and staff at the opening of the 1987-88 academic year, Swanson announced that he would retire on March 20, 1988 - the 80th anniversary of the signing of the Articles of Incorporation that created the Stout Institute. During Swanson's administration, Stout solidified its growth, reaffirmed its special mission and prepared a firm foundation for future challenges. In that address, Swanson noted that: "Growth changed Stout, but beyond the statistics, there were other social, educational and economic factors that profoundly influenced the university. The energy crisis, affirmative action, evaluation week, Title IX, minority recruitment, sexual harassment, OSHA, handicapped access and hazardous wastes were a few of the issues. Because Stout responded to those issues, it is a better place today. Policies are more efficient and fair. This does not mean that Stout is closing the door on further progress in those areas. It means that Stout has established a positive attitude to build on."

A screening committee searched nationally for more than a year before selecting a successor. In the interim, the UW System Board of Regents named Wesley Face the acting chancellor.

Face was no stranger to Stout. In his more than 30 years of service to the institution, he had been the chair of the metals department, a staff member on the American Industry project, assistant dean of the Graduate School, and vice chancellor. Through his professional involvements, his leadership extended beyond Stout. In his role as acting chancellor, he assured a smooth transition.

--Kevin Thorie

As the university moved toward its second century, Stout was strengthening its traditional connection to the needs of the marketplace. A proposed engineering program promised to raise the university's historic ties with industry to a new level. The newly-developed Stout Technology Park furthered the relationship, connecting the university's programs with the immediacy of the workplace.

The appointment of Charles W. Sorensen as the sixth head of the institution seemed almost a total break with the past. For the first time in more than 40 years, the institution would be headed by someone who had not graduated from Stout. Fryklund, Micheels and Swanson all had degrees from Stout and each had a strong background in industrial education. Harvey and Nelson before them, though not Stout graduates, had been leaders in industrial and vocational education. Sorensen was a historian. At first some people questioned if he would appreciate the university's distinctive role in Wisconsin's system of higher education. He soon made it clear that he came to the university with an understanding of Stout's heritage, and a desire to continue to update the institution's programs while maintaining its unique mission.

The appointment of Charles W. Sorensen as the sixth head of the institution seemed almost a total break with the past. For the first time in more than 40 years, the institution would be headed by someone who had not graduated from Stout. Fryklund, Micheels and Swanson all had degrees from Stout and each had a strong background in industrial education. Harvey and Nelson before them, though not Stout graduates, had been leaders in industrial and vocational education. Sorensen was a historian. At first some people questioned if he would appreciate the university's distinctive role in Wisconsin's system of higher education. He soon made it clear that he came to the university with an understanding of Stout's heritage, and a desire to continue to update the institution's programs while maintaining its unique mission.

Sorensen was born in Audubon, a small town in western Iowa. The family moved to Davenport, Iowa when he was one year old, and then to Moline, Illinois three years later.

Generally, young men and women growing up in the Moline area in the 1940s and '50s did not go on to college. Most took jobs at John Deere or at one of the other manufacturing plants in the area. Sorensen confessed that he was not an ideal student. But after working for a summer, he decided there had to be "a better avenue to a better life."

He attended Black Hawk Community College, and earned a bachelor of arts degree in history and political science from Augustana College in 1964. After a brief teaching assignment in Colorado, he began graduate work at Illinois State University, earning a master's degree in 1967. He earned a Ph.D. in American history from Michigan State in 1973.

The foundation for Sorensen's administrative career was shaped at Grand Valley State College in Michigan. He began teaching there in 1970, and after several promotions, was named dean of the College of Arts and Sciences in 1979.

In 1984, he was named vice president for Academic Affairs at Winona State in Minnesota. Four years later, on June 10, 1988, the UW System Board of Regents appointed him chancellor of University of Wisconsin-Stout. He began serving in August.

In his inaugural address, Sorensen said he saw "no pressing need for a dramatic change in the mission of UW-Stout." However, he outlined the challenges he said he believed the university must meet to maintain its leadership role. Among the most important was a strengthened relationship between the university and business and industry.

With the construction of the Stout Technology Park, the university moved into a dynamic new era in economic development. Sorensen noted that the park was a continuation of Stout's record of public service to the private sector: "Since its founding, Stout has had a valued tradition of meeting industry needs. The technology park truly symbolizes that tradition; here the past comes face to face with the present and with a host of new opportunities for the future. It is our challenge to develop those opportunities so that they return the highest possible rewards."

Sorensen recognized that Stout had to make a special effort to bring minorities to its campus. A medium-sized Midwestern university, located in a fairly rural setting, doesn't guarantee students the opportunity to meet people with other cultural or ethnic backgrounds. Yet Stout graduates frequently work in setting that require an understanding of the differences among people. Increasingly, the university is involved with international relationships, including economic and educational connections with China, Turkey, Malaysia, Bolivia, Saudi Arabia, and many other countries.

In his inaugural address, Sorensen pledged his commitment to recruiting more minority students and staff, saying that it was not only a moral and ethical obligation, but an absolute necessity: "A diversified campus is a healthy campus in every respect - body, mind and spirit. Healthy because the real world - the world of work and the world we send our graduates to - is a world of many colors and many races. We must prepare our students for diversity."

Sorensen also called for new emphasis on skills that prepare students to manage change. With the rate of change in our world, he said students must have computational and communication skills. Graduates must be capable of critical analysis and creative problem solving.

Sorensen began his tenure faced with a host of challenges from within and outside the university. But the university has always faced challenges. It grew and matured through two world wars, the Great Depression, and the unprecedented increases in enrollment and programming during the 1960s. The university will meet its current changes, as it has in the past.

From the start, the goals of Sorensen expressed for the university complemented not only the mission of the institution, but the goals of the leaders before him: "Each succeeding chancellor has had his dream for Stout and I have mine. It is for a university where ideas thrive, where intellectual curiosity leads people to new experiences, where the love of ideas meets the need for practical application, where learning is real and where quality education is simply not a cliché."

--Kevin Thorie